Sneak peek of Francesco Spampinato’s article on post-punk and TV in Italy out on CinémaCie https://www.cinemaetcie.net/issue33/. This issue on music and visual media has been edited by Simone Dotto, Francois Mouillot, and Maria Teresa Soldani. More than other music-driven subcultures, post-punk stands out as a proper transdisciplinary, postmodernist avantgarde developing hybrid productions at the crossroads of music, visual arts, performance, and media.

[….] Italian post-punk’s relationship with television, which this article aims to map and explore, has been ambiguous, shifting over time from critique to complicity to autonomy. As a recurring subject of sonic and visual appropriations and parodies, for those who embraced the music video form, television also became the medium through which they developed metalinguistic forms of reflection.

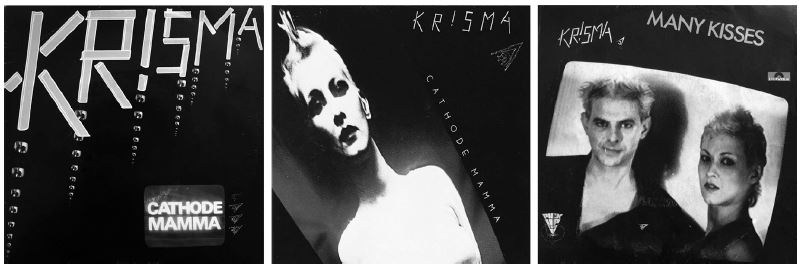

A quintessential case was that of Krisma – a duo composed of Maurizio Arcieri and Christina Moser, formerly known as Chrisma – who referred recurrently to TV in their lyrics, visual identity and music videos, but also made countless TV appearances, collaborated on TV programs and at some point even ran a TV channel. Their early thoughts on TV are summed up in the title-track of their 1980 album Cathode Mamma, whose lyrics state:

‘I like television sets because they have voices for when you are alone […].

Cathode mamma kiss me, in my cable paradise […].

I like television sets. They fill my empty rooms with electronic stone […].

They never go to sleep but glitter through the night [….]

They always stay at home and keep my bed so warm’.

Krisma’s song describes the TV set as a maternal presence in the home, able to keep company to the lonely viewer as if it was a real person. The 7-inch record cover, conceived by visionary art director Mario Convertino, shows seven flows of TV sets, each broadcasting an image of Christina, dropping down from the letters that form the band’s name and disappearing into a dark void.

Portraits of the musicians taken from a TV screen appear on the cover of the album and the popular single Many Kisses. The duo had already played with similar issues in 1979, via the 16mm promo for the song Aurora B. – when they still went by the name of Chrisma – directed by Sergio Attardo, which in fact could be considered one of the earliest ‘music videos’ ever produced in Italy. Scenes of the two in erotic moments that end with Maurizio’s attempted suicide alternate with scenes of Christina in a dark room, singing behind TV sets that transmit her live image, while another one broadcasts the footage of a Formula 1 incident, before setting on the Rai test pattern that appeared on the screen when no programming was broadcast, usually at night.

The Rise of Music Videos: The Peculiar Case of Mister Fantasy

[…]. Active until 1984, in its 100 episodes the program featured also 80 original music videos produced in-house, alongside music videos mainly from the US and the UK. Although these were mostly made for Italian pop singers and songwriters, and a handful of post-punk acts, Mister Fantasy was not only responsible for bringing the post-punk aesthetics to TV: inspired by the post-punk milieu, it also manufactured a postmodernist Gesamtkunstwerk in the form of a commercial product.

This, however, had a double effect: while challenging the language of TV, it also helped to reinforce its persuasive power. Indeed, on the one hand Mister Fantasy broke with traditional notions of media entertainment and turned mainstream television into a context for artistic expression and experimental communication. On the other, the program exemplified what Umberto Eco called ‘Neo-Television’, a new type of television that emerged in the 1980s, which was self-referential, based on an obsessive audiovisual flow, the juxtaposition of different layers of communications and, precisely, the convergence of various media.

At the core of Neo-TV, as media scholar Gianni Sibilla argues, the music video is based on a kaleidoscopic merging of various elements and ‘is aware of its role, its position within the music and audiovisual context and does not miss the opportunity to expose its proper communication modes’. Interestingly enough, some music videos produced by Mister Fantasy adopted self-referentiality as a deconstructionist tactic as in the case of the 1982 video trilogy realized for Krisma’s songs, by a team that included the video directors Piccio Raffanini and Attardo, the photographer Edo Bertoglio, and the art director Convertino.

Filmed in Bali, the trilogy opens with the Miami video, based on a scene with Maurizio wondering on a paradise beach, armed and threatening, intercut with flashes of a TV set tuned to the new-born channel Rete 4 broadcasting the Vietnam War movie The Soldier’s Story (Ian McLeod, 1981). The anti-war ethos, based on the dichotomy beauty/cruelty, persists in the videos of Water and Samora Club, where Christina’s glamour clashes with the shadows of a submarine in the first, and of Maurizio in military attire and anxious to use his knife in the latter.

Along with this explicit anti-war reading, another interpretation emerges: in manufacturing a hyperreality based on criteria of entertainment and advertising, television desensitizes its audience regarding the world’s real problems such as war, notably the Cold War that was ongoing at that time, while producing subtle forms of propaganda. By juxtaposing original scenes with TV footage and Convertino’s infographics, exposing elements of the backstage (e.g. a backdrop) and playing on the ambiguity between reality and its double (e.g. the shadows), this trilogy elicits a metalinguistic reflection on the media’s power to manipulate reality. Mister Fantasy produced also the video for Krisma’s I’m Not in Love (1984), directed by Giancarlo Bocchi, although this was less concerned with television per se than the propaganda of totalitarian regimes at large. Along with Krisma, the only other ‘proper’ post-punk act featured in the program was Garbo. Out of the three music videos produced for him by Mister Fantasy, the one for Radioclima (1984), directed by Raffanini, is characterized by the presence of radios and TV sets, alluded to as media able to produce stereotypes with which the audience unwillingly identifies.

Francesco Spampinato, Alma Mater Studiorum – Università di Bologna

https://www.cinemaetcie.net/issue33/

Lascia un commento